Definition of carbohydrates, or "slow and fast sugars

Carbohydrates are energy providers the body's preferred nutrients, i.e. the nutrients from which the body will draw its energy. energy preferentially and quickly.

Note: this article is one of the chapters in the Blooness feeding guidea guide to the ingredients of the ideal diet for humankind.

Carbohydrates are transformed by the body into glucose to produce the energy molecules known as of Adenosine TriphosPhate alias ATP. The effectiveness of this process depends very much on vitamins and minerals present in carbohydrates; this is why foods rich in "bad" carbohydrates and devoid of natural vitamins and minerals, such as industrial sweets, result in degraded energy production.

This content is part of the guide Blooness, the guide to the ideal human diet, the summary of which you can find here 🌱🥑

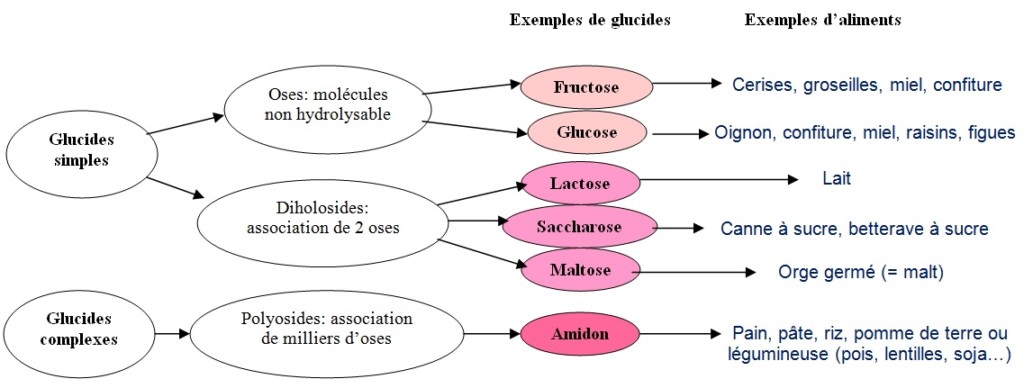

Depending on their chain length, carbohydrates are classified as follows:

- monosaccharides: glucose, fructose (fruit sugar) and galactose (milk sugar)

- disaccharides: sucrose (industrial sugar, made up of glucose and fructose), lactose (carbohydrate found in mammalian milk)

- oligosaccharides: raffinose (composed of one galactose unit, one glucose unit and one fructose unit)

- polysaccharides, also known as complex carbohydrates: amylopectin (plant starch), glycogen (animal starch), inulin (produced by many types of plant). Polysaccharides are in fact fructose-type sugars linked together.

The first three groups of carbohydrates belong to the simple carbohydratesfamily, while the last group belongs to the complex carbohydrates. Before we understand the difference between these two types of carbohydrate, let's take a moment to look at the confusion between sugars and carbohydrates, and the words "including sugars" found on consumer product labels.

Take control of your diet and never miss another chapter of the guide by subscribing to the Blooness newsletter 🙌

The difference between carbohydrates and sugars

Consumers are currently confused between the terms "sugar" and "carbohydrate". We often tend to confuse the two, for two very different reasons:

- Sugar in the strict sense of the term belongs to the carbohydrate family, but it's not the only one. not all carbohydrates are "sugars". strictly speaking. It's a question of belonging, not equivalence, which leads to confusion between the two.

- On the other hand, some people tend to refer to all carbohydrates as "sugars" in order to simplify things, but they don't consider this to be a mistake. In this case, "sugars" don't necessarily refer to everything that tastes sweet, but simply to carbohydrates, which are a combination of sugar molecules that don't necessarily taste sweet as we know it.

Let's clarify things, and take as a reference what is indicated on the labels of the products we buy at the supermarket. These labels indicate sugar as the smallest link in a carbohydrate chain, i.e. simple carbohydrates, as opposed to complex carbohydrates.

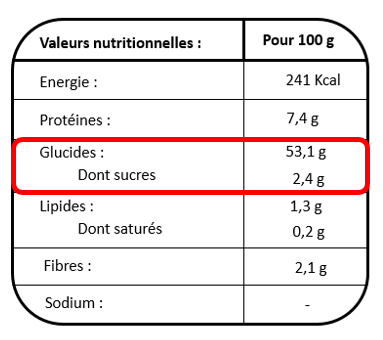

On these labels, the word "carbohydrates" indicates the total amount of carbohydrates (simple carbohydrates + complex carbohydrates). Of which sugars" refers only to the quantity of simple carbohydrates.

Products labelled in accordance with European standards indicate a total carbohydrates, which includes all sugars (slow and fast, or simple and complex, are the terminologies), while visit fibers low-calorie foods - are in a class of their own. Conversely, if you're shopping in North America, fiber is included in the carbohydrate total, so you'll need to deduct fiber from the carbohydrate total to get the exact amount of carbohydrate that will be metabolized by the body and therefore converted into energy or fat reserves.

For a sedentary person, the challenge is to reduce the quantity of simple sugars, if possible, in favour of complex sugars, and the quantity of complex sugars, in favour of fibre, vitamins and minerals. proteins and, to a certain extent, fats, in order to preserve its natural insulin and not overfeed your body with unnecessary energy.

Example of a label to decipher:

In this example, taken from the label of a spread from a well-known brand of dietary supplements, the carbohydrate content amounts to 31 grams per 100 grams of product. There are 7 grams of sugars (simple sugars), and 23 grams of polyols. A polyol is a sugar alcohol, but does not contain alcohol; it's just an industrial sweetener used to give a sweet taste to a product, without adding glucose or fructose, for example. Depending on the type of polyol used, their consumption often has a limited effect on the blood glucose.

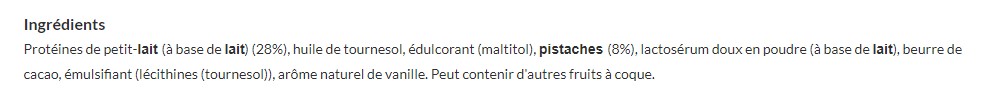

In this case, a check of the ingredients list reveals that the polyol used is maltitol:

Maltitol does have an effect on glycemia and therefore on insulin response, since it has a GI of 25 to 35. It is therefore not recommended for dieters. ketogenicMaltitol is not a sweetener, but it is tolerated in a low-carb diet, even though sweeteners are generally to be limited as part of a healthy lifestyle and a diet based on unprocessed products. What's more, maltitol also contains three-quarters of its calories as sugar. In reality, it is only partially digested by the body, and therefore has a much less impactful effect than table sugar, but it still contributes calories. What's more, maltitol causes mild digestive symptoms when generously consumed (gas and bloating).

To simplify things as much as possible, we can consider that in this example, the product is not extremely rich in carbohydrates, the 7 grams of sugar being very limited to have an energy impact, but on the other hand, the sugar substitute used is to be watched, because if there are no starch or complex sugars in the "Carbohydrates" part, there are all the same 23g of polyols which are not necessarily advised within the framework of a healthy life and a natural low-carb diet. Nevertheless, it remains a decent product for occasional indulgence without causing insulin spikes.

The difference between simple and complex carbohydrates

As we explained earlier, there are two main families of carbohydrates. Simple ones, also known as "fast sugars", and complex ones, more commonly known as "slow sugars".

Definition of simple carbohydrates, or "fast sugars", or "sugars".

Visit simple carbohydrates, also known as "sugars" on consumer product labels, are small molecules (low molecular weight) with a sweet taste. They are glucose, fructose, lactose, maltose, galactose or sucrose. They generally get a bad press, but it's important to differentiate between simple carbohydrates from fruit, which are relatively low in quantity, and simple carbohydrates from industrial products.

Simple carbohydrates are also known as "fast sugars" because their consumption leads to very rapid absorption by the bodyThe result is a rise in blood sugar, which in turn triggers insulin secretion to regulate sugar levels, and storage of reservesThis can lead to weight gain over the medium and long term. More on this later.

Because they are quickly absorbed into the body, fast sugars are sometimes used during intense effort to boost the body's performance, or simply for their highly appreciated taste. That's why it's common practice to give sugary drinks or sweetened chocolate bars to students during exams, to accompany cerebral effort, or during muscular exertion. But we'll see later that this method is increasingly being called into question in the field of nutrition.

Foods rich in simple carbohydrates or quick sugars

Simple carbohydrates are found in almost all fruits: apples, cherries, kiwis, melons, oranges, peaches, etc... But also in sweets and pastries: sugar, cakes, cookies, jam, chocolate, candies, sodas, etc...

Definition of complex carbohydrates, or "slow sugars

Visit complex carbohydrates are very large molecules (high molecular weight) with no sweet taste, including :

- maltodextrins: a combination of several carbohydrates derived from the hydrolysis of wheat or corn starch.

- fructo-oligosaccharides: composed of two simple sugars, glucose and fructose.

- starch: a mixture of two polysaccharides, amylose and amylopectin. Polysaccharides are complex carbohydrates made up of a large number of simple sugars, linked together by glycosidic bonds.

- cellulose: a polysaccharide made up of numerous glucose molecules, and which is a fiber part of the plant structure.

- pectins: an acidic polysaccharide found in plants and used as a gelling agent.

- and fiber: starchy polysaccharides not broken down by digestive enzymes.

Fiber is therefore also a carbohydrate, and a fortiori a complex carbohydrate, with the difference that it is not absorbed by the body. They therefore provide few or no calories.

Complex carbohydrates are also called "slow sugars" because they are absorbed into the body more slowly than simple carbohydrates, so they provide a steady supply of energy throughout the day.

Foods rich in complex carbohydrates or slow sugars

Visit foods rich in complex carbohydrates are mainly wholegrain products such as wholemeal breads, oats, muesli and wholegrain rice:

- Bran, Wheat germ, Barley

- Corn, buckwheat, semolina, oats

- Pasta, Wholemeal rice, Potatoes

- Vegetables roots

Wholemeal bread, Grain bread - Wholegrain cereals

- High-fiber breakfast cereals

- Muesli

- Cassava

- Peas, Beans, Lentils

To put it as simply as possible:

- Simple carbohydrates, or "fast sugars", such as glucose, fructose or sucrose, are easily found in fruit and sweets. This is sugar in the common sense of the term, as we know it, and what we often call "fast sugars".

- Complex carbohydrates, better known as "slow sugars", correspond to the assembly of several simple carbohydrates, and are found in cereals, starches and side dishes commonly consumed around the world.

About the glycemic index of carbohydrates

Definition of glycemic index

You've probably heard of glycemic index (GI). This value system classifies carbohydrates (on a scale of 0 to 100) according to the speed with which glucose enters the bloodstream. The higher the GI value, the faster glucose enters the bloodstream after ingestion.

Our body reacts to this rise in blood sugar by secreting a hormone: insulin. This hormone is responsible for penetrate glucose into our cells to reduce circulating blood sugar levels. This is because the body can only tolerate a certain level of sugar circulating in the blood, known as glycemia. A hormone called insulin is responsible for getting the sugar circulating in the blood into the cells, thereby lowering blood sugar levels to normal levels for the body.

Over time, the repetition of this process can contribute to a decrease in insulin sensitivity, and thus reduce the effectiveness of insulin in delivering glucose to cells. This is the first step towards type 2 diabetes.

What's more, over-consumption of carbohydrates could encourage inflammation, paving the way for chronic disease, as well as fat storage.

That's why official nutritional recommendations recommend eating low or moderate GI carbohydrateswhich do not generate large insulin peaks.

Low and moderate glycemic index foods

- Fruit, as much for its moderate GI as for its natural, protective nutrients, but eat in moderation.

- Tubers (quinoa, buckwheat, chestnuts, sweet potatoes, etc.).

- Wholegrain cereals, especially basmati rice.

- Visit pulseslike lentils or chickpeas, which are the "flagship" carbohydrates in terms of health, and correspond to the Mediterranean diet. We'll come back to this later.

In addition, accompanying carbohydrates with fiber will slow down their absorption. We'll look at fiber in the next chapter.

What is the recommended daily carbohydrate intake?

It is important to know that carbohydrates are stored in the body in two ways:

- in the form of glycogen in the liver (⅓)

- in the muscles (⅔).

These glycogen reserves are used by the body as a source of energy during physical effort. and are then fueled by a carbohydrate-rich diet.

But beware, again simplifying things as far as possible: if there's no physical or mental effort, the carbohydrates ingested risk being overdosed for the body, which will then transform this surplus into fat stored as a reserve, which, unless you're looking to gain weight for the needs of a role in a film, is a priori not your objective, either aesthetically or health-wise.

Therefore, the recommended daily carbohydrate intake will depend on several factors:

- Your diet and lifestyle: if you have chosen a high-carbohydrate diet, it is advisable to use carbohydrates by expending energy throughout the day (professional sports, very physical work, etc.).

- Your beliefs and diet: whether you're a vegetarian, vegan, carnivore, etc...

- Your metabolism

- Your propensity to experience "carbohydrate crashes" after eating carbohydrates

- Your addiction to industrial sugars, which you should fight

- Your compatibility with a more or less moderate carbohydrate diet

- etc...

It's important to know that the public authorities recommend using consume around 50% of energy needs of an adult, giving priority to complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides), found in fruit, vegetables, legumes and well-known starchy foods (rice, wheat, potatoes, cereals...). Conversely, simple carbohydrates found in refined sugar, industrial sweets, soft drinks, etc. should be reduced.

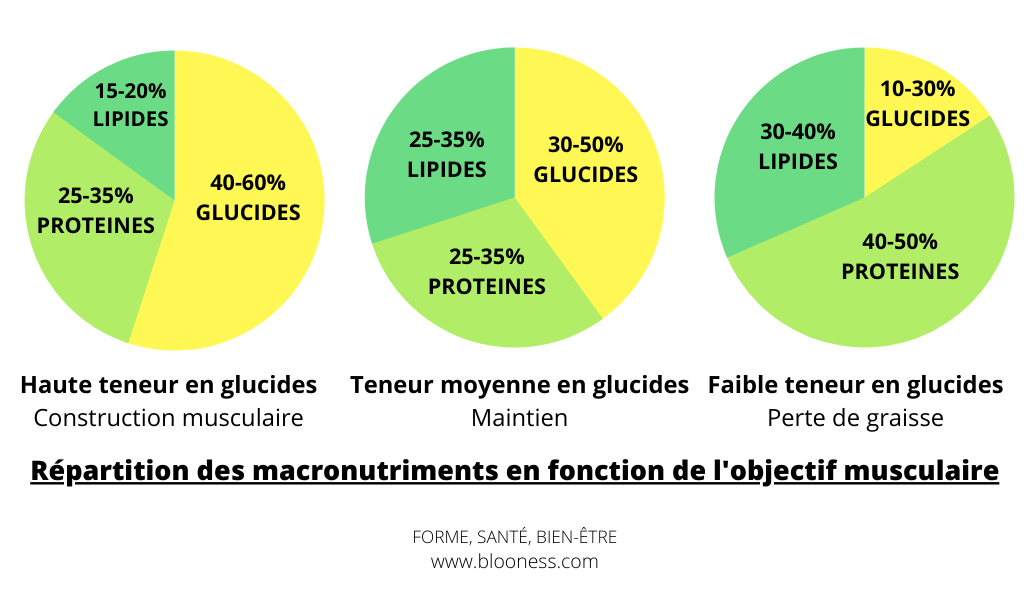

As we mentioned earlier, in the chapter on macro-nutrients in general, the carbohydrate content will often depend on your objectives (muscle gain, maintenance or lean) and your metabolism (propensity to gain body fat or not).

To better understand the distribution of macronutrients, it's interesting to look at what is generally practiced or recommended in the world of fitness or dietetics, depending on the expected objectives. This will give us a clearer idea of how carbohydrates have been consumed since the middle of the 20th century, beyond the pleasure they can provide through French fries or sweets, for example.

In this respect, there are three main known macronutrient distributions. Let's take a look at these three main breakdowns, and at the situations in which they are used:

These three main breakdowns are those familiar to the general public, based on sporting or lifestyle objectives. They are not necessarily the divisions we will be recommending later in the Blooness guideBut it's important to understand the common logic in order to move forward and find your own distribution.

- In general, athletes and non-sedentary people who have a very physical job all day long tend to opt for a carbohydrate-rich diet. In fact, this is what the authorities recommend, and not just for sportsmen and women, which is the subject of much debate. Proteins are obviously an important part of the diet, as they have an effect on muscle tissue. lipids are in the minority.

- Maintainers or semi-sedentary people will opt for a balanced distribution between the three macronutrients, in addition to relatively regular or at least occasional sporting activity.

- Finally, overweight people wishing to lose body fat generally opt for a high protein intake, a low carbohydrate intake and a high fat content, with, if possible, some sporting activity at the same time.

Here again, although each case is unique, we'll keep things as simple as possible:

- If you're looking to build muscle, it's often advisable to consume a high proportion of carbohydrates, especially on days when you're training. But we'll come back to this specific case later, in the chapter dedicated to low-carbohydrate sports nutrition.

- If you've got a good figure, and you're just looking to maintain the way you are, you'll often be advised to eat a "balanced" diet. This relatively generic term, which often means nothing, takes on its full meaning here: it's all about getting your share of carbohydrates, in roughly equal proportions with the rest.

- Finally, if you're the kind of person who puts on weight, and despite all your efforts you still have fat and are looking to sharpen up, cutting back on carbohydrates may be something to consider. Especially if, in the past, you've been a big sugar and carbohydrate eater, which may have altered your insulin sensitivity.

On the subject of high carbohydrate intake for athletes

Sedentary urban dwellers are accustomed to consuming hundreds of grams of carbohydrates every day.

Between breakfast, made with bread, jam, sometimes spread, sweet cereals, orange juice, etc., lunch, which is often in the form of a sandwich, or a dish with a high proportion of starchy foods (rice in a Japanese restaurant, French fries in a brewery, etc.), and dinner, delivered or in a restaurant, or spaghetti prepared at home, we tend without realizing it to 300 to 600 grams of carbohydrates per day. And that's not counting the beer after work.

However, "mass gain" dietary programs aimed at bodybuilders are based around 300 to 500g of carbohydrates per day. This intake is intended for a person who is then going to carry out an intense effort, often close to weightlifting, and sometimes with an additional cardio or split effort.

The question to ask is: is it normal for the carbohydrate intake of a sedentary person who practices a sport occasionally, at the weekend for example, to be almost the same as the carbohydrate intake of a body-builder? What about the consequences of ingesting such a large quantity of carbohydrates without eliminating them in the hours that follow?

We'll be coming back to this issue shortly, as part of the Blooness feed...

How much energy do carbohydrates provide?

In terms of calories, just like proteins, 1 gram of carbohydrates corresponds to 4kcal, compared to 9kcal for 1 gram of lipids. This is an important notion to bear in mind when considering the number of calories to ingest and expend each day.

The special case of fibers

Fiber, found in vegetables, is also a carbohydrate, and a complex one at that. So complex, in fact, that they are not absorbed by the body: they simply slow down the absorption of other carbohydrates, enabling a more even distribution of energy, while providing no calories. What's the point of eating them, you may ask?

To answer this question, let's tackle the chapter reserved for them...

Next chapter: all about fibers

Previous chapter: macronutrients: official nutritional recommendations